Photoplethysmography, or PPG, is the optical foundation of most wearable HR and HRV measurements. By shining light into the skin and measuring tiny changes in reflection, these sensors estimate pulse timing and beat to beat variability. In lab conditions, they perform extremely well. In real life, their accuracy depends on physics, physiology, and how people actually move.

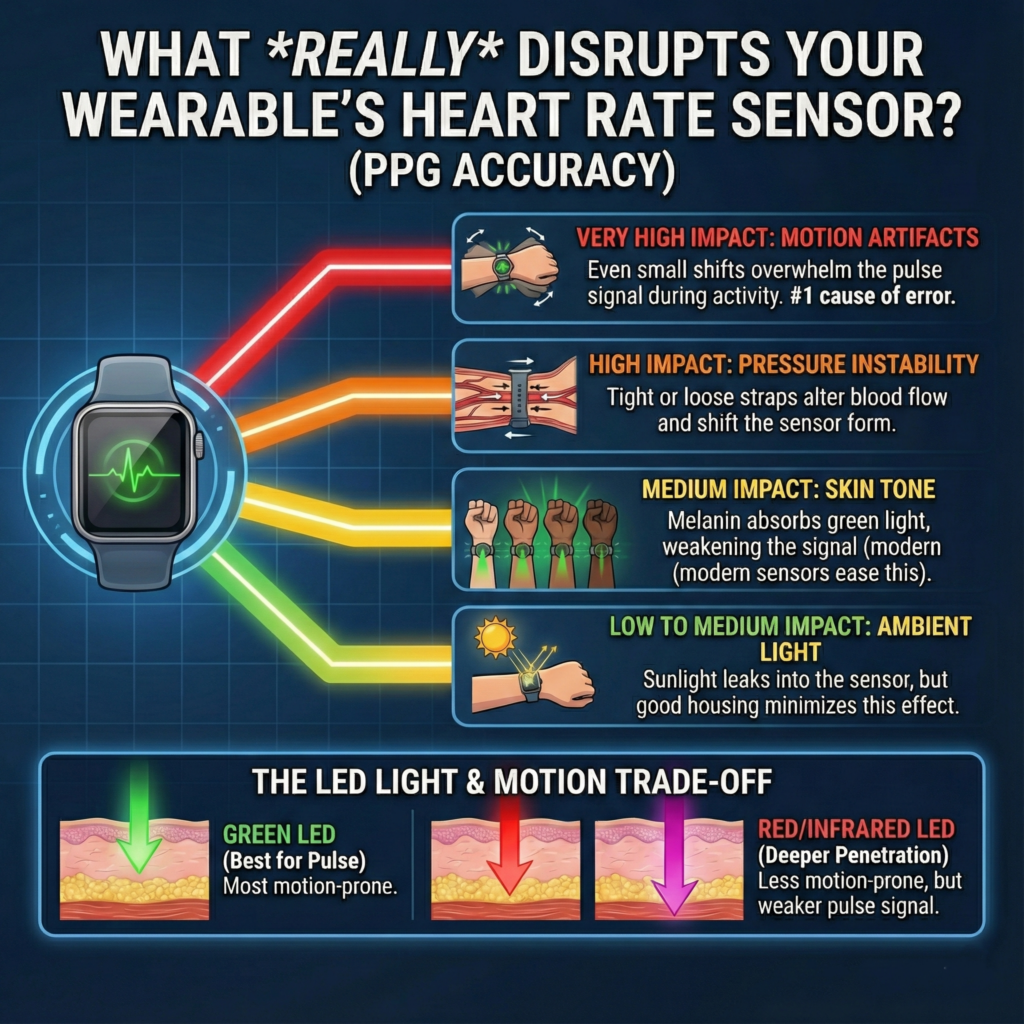

The figure below frames the question many users ask when their HR or HRV data looks unreliable.

The following figure addresses a common user concern regarding the perceived unreliability of their heart rate (HR) or heart rate variability (HRV) data.

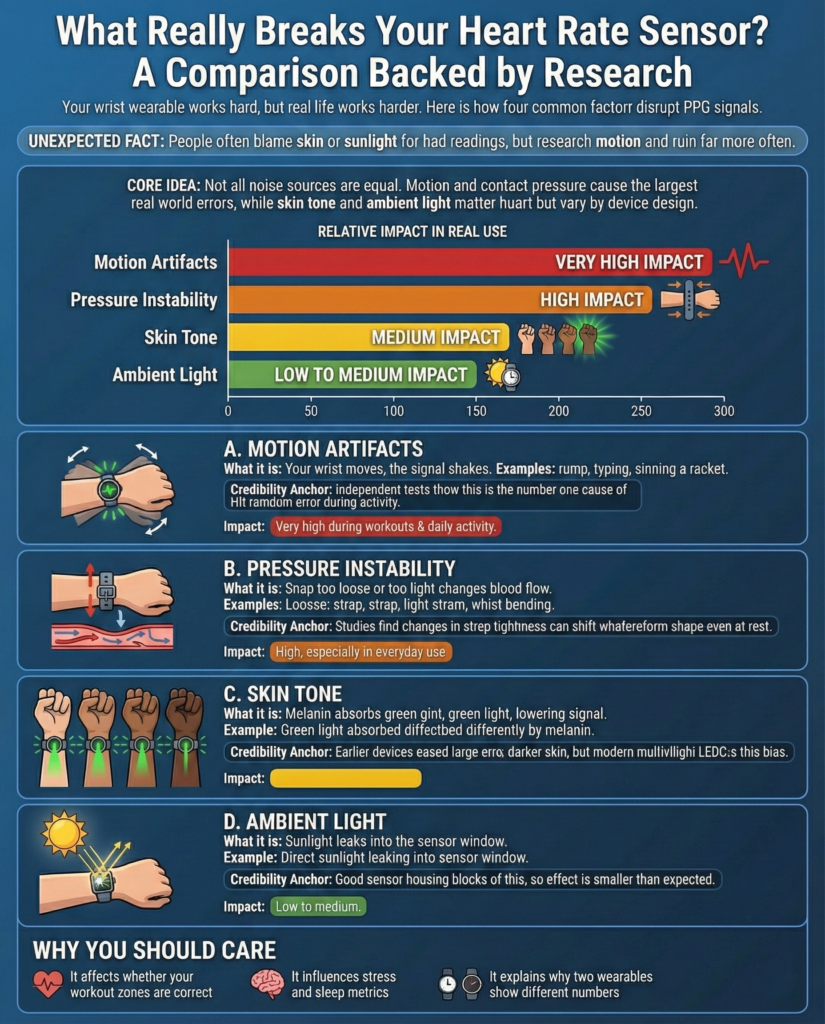

Four factors are commonly blamed for errors in HR and HRV: motion artifacts, pressure instability, skin tone, and ambient light. All four matter, but they do not contribute equally.

When evidence from validation studies and free living measurements is compared, a clear hierarchy emerges.

This figure summarizes that hierarchy.

The hierarchy is summarized in this figure.

Motion artifacts dominate real world HR and HRV error.

Even subtle wrist movement introduces timing noise that can exceed the pulse signal itself. Because HRV depends on precise beat to beat intervals, it is especially vulnerable to motion related distortion during activity.

Pressure instability is the next largest contributor.

Strap tightness affects local blood volume and sensor contact. Small changes in pressure can shift waveform morphology, degrading both heart rate stability and HRV metrics, even when the wearer is otherwise still.

Skin tone has a smaller but measurable effect.

Melanin absorbs green light and reduces signal amplitude. While this can increase noise floor, modern multi wavelength designs and signal processing substantially reduce skin tone dependent bias compared to early devices.

Ambient light has the lowest relative impact.

External light interference exists, but optical shielding and filtering make it a secondary concern for most modern wearables.

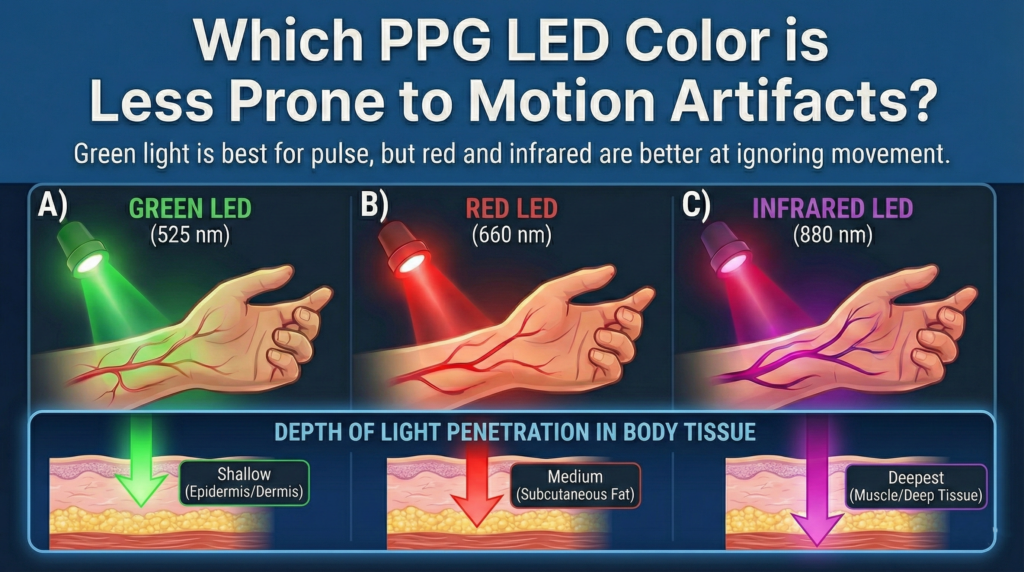

Why does motion disrupt HR and HRV so severely? The answer lies in wavelength physics, shown in the figure below.

The solution, illustrated in the figure below, is rooted in the physics of wavelength.

reen light, around 525 nm, is strongly absorbed by blood, producing a clear pulse waveform at rest. However, it penetrates only shallow tissue layers. Surface level movement, muscle contraction, and skin deformation introduce large timing noise that overwhelms beat detection.

Red and infrared wavelengths penetrate deeper into tissue and are less sensitive to surface motion. While their pulse amplitude is lower, their stability makes them invaluable during movement.

This is why modern wearables rely on multi wavelength PPG. Red and infrared signals act as motion robust references, allowing algorithms to detect and suppress motion noise in the green channel. This improves not only average heart rate, but also the beat timing accuracy required for meaningful HRV.

The takeaway

HR and HRV accuracy in wearables is not limited by a single sensor or demographic factor. It follows a hierarchy dominated by motion and contact mechanics, shaped by optical physics and human behavior. Understanding this hierarchy is essential for interpreting wearable data correctly and for building systems that perform outside the lab.

At Centralive, this perspective guides how we analyze HR and HRV data, treating every signal as a product of real world physiology and movement, not just sensor specs.